In this section

1791–1892: One step forward, two steps back…

In Lower Canada, the Constitutional Act of 1791 granted some landowners qualified voter status with no distinction as to gender. Some women in Lower Canada who met the requirements interpreted this constitutional “oversight” as permission to vote and apparently became the only women in the British Empire to exercise that right. However, the times were not propitious for the recognition of women’s rights, and in 1849, under the Baldwin–LaFontaine ministry, this “historical irregularity” was rectified by formally prohibiting women from voting.

In 1892, however, Quebec’s Conservative premier Charles-E. Boucher de Boucherville spearheaded the passing of legislation granting single and land-owning women and widows the right to vote in municipal and school elections, so long as they did not run as candidates themselves.

1912–1922: The birth of the suffragist movement

In Canada, the first suffragettes association, the Women’s Suffrage Society, was created in 1883. In Québec, it would not be until the 20th century that a true movement for women’s right to vote would emerge. In 1912, the Montreal Suffrage Association mobilized its forces to fight for the right of women to vote in federal elections. This right was granted in 1918.

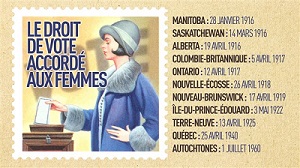

Suffragettes were also active in the other Canadian provinces. Manitoba became the first province to grant women the right to vote in 1916, followed the same year by Saskatchewan and Alberta. In 1917, British Columbia and Ontario followed suit. Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island granted the right to vote in 1918, 1919 and 1922. For its part, Newfoundland and Labrador, which joined Canada in 1949, granted women the right to vote in 1925. Only the women of Québec were still excluded from voting in provincial elections.

Source: Radio-Canada Manitoba

1922–1940: Suffragettes crusade for equality

Activists organize

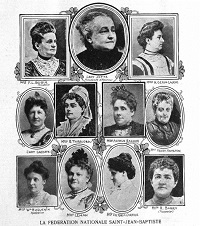

The Québec suffragist movement was essentially an urban phenomenon and the initiative of a minority of women who were ahead of their time. The Comité provincial pour le suffrage féminin (Provincial Committee for Women’s Suffrage) was created in 1922. Most of its members came from the Montreal Suffrage Association and the Fédération nationale Saint-Jean-Baptiste (Saint-Jean-Baptiste National Federation). English-speaking and French-speaking activists joined forces for the same cause. Initially, the committee was co-chaired by Marie Gérin-Lajoie and Mrs. Walter Lyman, until the group split up in 1927. From that point on, the suffragist movement was led by two women:

- Idola Saint-Jean, with the Alliance canadienne pour le vote des femmes au Québec (Canadian Alliance for Women’s Vote in Québec);

- Thérèse Casgrain, with the Comité du suffrage provincial (Provincial Suffrage Committee), which in 1929 became the Ligue des droits de la femme (League for Women’s Rights).

In addition to being active with these organizations, the two women continued to break down barriers by getting involved in political life and running as candidates at the federal level. Supported by working women, Idola Saint-Jean became the first French-speaking woman in Québec to run as a candidate, doing so as an independent Liberal in the riding of Saint-Denis during the 1930 federal election. Thérèse Casgrain, for her part, stood for election in 1942 in the federal riding of Charlevoix-Saguenay, also as an independent Liberal. While Thérèse Casgrain was defeated nine times in provincial and federal elections between 1942 and 1962, she would become the first woman to lead a Québec political party when she was elected to head the provincial wing of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) in 1951.

First board of directors of the Fédération nationale Saint-Jean-Baptiste (FNSJB). Source: FNSJB website

Adversaries

The quest for democratic freedoms was long: the road was paved with many pitfalls and there were numerous adversaries. The clergy, politicians, journalists, most women, in short, society in general did not subscribe to the idea of seeing Québec women become full-fledged citizens. At that time, for most opponents, this meant the end of a society founded on the exclusion of women. The Civil Code, adopted in 1866, had entrenched this exclusion, and had also confirmed the legal incapacity of married women. In other words, women did not enjoy the same legal rights as men.

For the most part, the arguments against giving women the right to vote were centred on their place in the home and their role as guardians of the French-Canadian race. The following statements are a good reflection of the obstacles and biases that confronted suffragettes:

“The entry of women into politics, even if only by suffrage, would be a misfortune for our province. Nothing justifies it, neither natural law nor the social interest; the authorities in Rome approve of our views, which are those of our entire episcopate.” (Cardinal Bégin; Source: Cap-aux-Diamants, No. 21, Spring 1990, p. 23).

“Were this bill to pass, women would resemble a star having left its orbit.” (L.-A. Giroux, legislative councillor [Wellington]; excerpt from the April 25, 1940 Legislative Assembly debates).

“[…] French-Canadian women risk becoming ‘public women’ […], veritable women-men, hybrids that would destroy women-mothers and women-women.” (Henri Bourassa, founder of the daily newspaper Le Devoir, Source: Cap-aux-Diamants, No. 21, Spring 1990, p. 20).

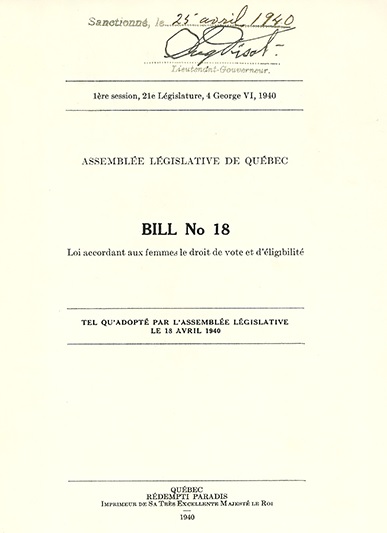

National Assembly record: Débats sur la Loi accordant aux femmes le droit de vote et d’éligibilité. Source: Chief Electoral Officer collection.

Battle strategy

This was the context in which women struggled to acquire the right to vote. The battle was waged on two main fronts:

- Activists launched media operations targeting the general public. Public protests, the use of the media and skillfully orchestrated information campaigns allowed the suffragist movement to gradually change mindsets and rally public opinion, which had initially been largely resistant. On the 25th anniversary of the reign of King George V in 1935, suffragettes sent him a petition with 10,000 signatures in favour of women’s suffrage in Québec.

- Activists lobbied the members of the Québec Legislative Assembly. Every year, they found a legislator who supported their cause to sponsor bills on suffrage. Legislator Henry Miles agreed to introduce the first of these bills. Fourteen bills were tabled before the last one was finally passed.

Supported by Premier Joseph-Adélard Godbout, Bill 18 was passed on April 18, 1940, by a vote of 67 to 9. The Act granting to women the right to vote and to be eligible as candidates was given assent by the lieutenant-governor on April 25, 1940, finally putting an end to electoral discrimination against women at the provincial level.

“Give women a liberating vote and open the doors to the political arena for women from here so that they may participate in provincial life with as much dignity as in federal life where they have participated for over twenty years.” Idola St-Jean in 1939, speaking before the members of the National Assembly.

Cover page of the Act granting to women the right to vote and to be eligible as candidates, given assent on April 25, 1940. Source: National Assembly website, Par ici la démocratie

1940–2020: 80 years later

April 25, 1940 marked the end of a hard-fought struggle and the beginning of a new era. From then on, women could vote and stand as candidates, but the next challenge for women would be to get elected. While no women ran in the 1944 election, the first female candidate, Mrs. Dennis James (Mae) O’Connor, ran in the July 23, 1947 by-election in the Huntingdon riding.

It was not until 1961 that women would have a voice in parliament, that of Marie-Claire Kirkland-Casgrain. The first woman to become a Member of the National Assembly and the first woman to be named a minister, she advanced the cause of women by tabling a bill which, in 1964, put an end to the legal incapacity of married women. At the municipal level, women gradually obtained the right to vote between 1968 and 1974, depending on the city or municipality. First Nations women living on reserves have had the right to vote in Québec since 1969.

Marie-Claire Kirkland-Casgrain, the first woman to be elected and the first woman to serve as a minister. Source: Library and Archives Canada

However, despite of the legislation passed in 1940, a significant female presence would not be felt in the National Assembly until the 1980s. The general election of 1976 marked the first time that more than one woman was elected to the National Assembly: five women were elected at that time, followed by eight in 1981. Women would have to wait until 1985 to constitute more than 10 female MNAs with 18 women elected in the 1985 general election and 23 in both 1989 and 1994. In 1998, a total of 29 women were elected to the National Assembly, representing 23.2% of all seats.

In the 2000s, women’s representation in the National Assembly seemed to hit a ceiling. Women made up 30.4% of all elected MNAs in 2003, 25.6% in 2007, and 29.6% in 2008. After reaching the historic threshold of 32.8% in 2012, the percentage of women in the National Assembly dropped to 27.2% in the 2014 election.

In 2007 and 2008, Premier Jean Charest formed the first cabinet in which men and women were equally represented, a level of parity not seen since. Then in the 2012 election, Pauline Marois was elected Québec’s first woman premier.

Pauline Marois, the first woman to serve as Québec Premier. Source: Québec National Assembly website

Moreover, in the 2018 provincial general election, Québec set two new records for political representation by women. First, there were a record number of women candidates, namely 375 out of 940 candidates, or 40% of the candidates in the election. The number of women elected to the National Assembly was also a milestone. Fifty-three women were elected that year, constituting 42% of all MNAs.

The achievement of political equality and access to power for women has led to advances in legislation and the introduction of numerous measures that have helped Québec society move forward. Since the Québec Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms was adopted in 1975, discrimination based on gender has been prohibited. A number of other legislative advances deserve mention as well:

- Act respecting the Conseil du statut de la femme (1973)

- Act to amend the Civil Code of Québec and other legislation in order to favour economic equality between spouses (1989)

- Act to facilitate the payment of support (1995)

- Pay Equity Act (1996)

- Act respecting parental insurance (2001)

- Act to amend the Charter of human rights and freedoms “to expressly state that Charter rights and freedoms are guaranteed equally to women and men” (2008)

The struggle for women’s rights has been a gradual, step-by-step process. As Thérèse Casgrain put it when talking about women’s fight for universal suffrage: “Give it enough time and you can cook an elephant in a pot!” While equal rights were obtained, there is still ground to be covered for real equality to be achieved. The various actors in society continue their efforts in this direction.

Percentage of women elected to the National Assembly since 1976

Viewing mode

| Year | Percentage |

|---|---|

| 1976 | 4.50% |

| 1981 | 6.50% |

| 1985 | 14.80% |

| 1989 | 18.30% |

| 1994 | 18.30% |

| 1998 | 23.20% |

| 2003 | 30.40% |

| 2007 | 25.60% |

| 2008 | 29.60% |

| 2012 | 32.80% |

| 2014 | 27.20% |

| 2018 | 42.40% |

| 2022 | 46.40% |

Anniversary of Québec Women’s Right to Vote and Eligibility to Run as Candidates

- 1990: 50th anniversary

We published a study by France Lavergne on the representation of women in politics, entitled Le suffrage féminin. The study traces the main events that have taken place in Québec and provides a snapshot of the suffragette movement as it existed around the world. - 2000: 60th anniversary

On October 2, 2000, the Directeur général des élections du Québec (DGEQ), the Conseil du statut de la femme, the Commission de la capitale nationale and the National Assembly unveiled a poster based on a painting by Brigitte Labbé. “The artist, Brigitte Labbé, depicts a serene woman, a woman of no particular time or place, a woman ‘free to make her voice heard.’ The poster produced from this artwork is a tribute to all women, because there is no democracy without them.”

Poster by the artist Brigitte Labbé.

- 2005: 65th anniversary

On April 19, 2005, the Medal of the National Assembly was awarded to Madeleine Parent, representing all women who had fought for their right to vote. - 2010: 70th anniversary

The Québec National Assembly erected a monument to pay tribute to the women who had fought for the right to vote. Created by artist Jules Lasalle and depicting Idola Saint-Jean, Thérèse Casgrain, Marie Lacoste Gérin-Lajoie and Marie-Claire Kirkland, the monument stands in front of the Parliament Buildings’ southern façade and was unveiled on December 5, 2012. The Chief Electoral Officer of Québec’s research department published an article on the history of women’s participation (PDF – in French) in Québec elections in a special bulletin from the National Assembly Library on the occasion of this anniversary.

Source: National Assembly website, Par ici la démocratie

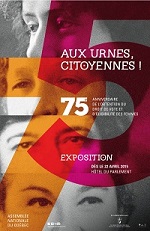

- 2015: 75th anniversary

To mark the 75th anniversary of women’s right to vote, DGEQ Secretary General Catherine Lagacé gave a speech at the opening of the National Assembly exhibition Aux urnes, citoyennes! on April 22, 2015.

Equality in law and equality in practice

In September 2014, the DGEQ published the report Femmes et politique : facteurs d’influence, mesures incitatives et exposé de la situation québécoise (PDF – in French). The study’s purpose was to provide input for an examination of factors influencing women’s participation in politics and review the measures put in place elsewhere around the world. The study also looked at the situation in Québec and made recommendations regarding the conditions necessary for increasing the number of women in politics in Québec. Among the conclusions, the study found that recruiting candidates is a key factor in ensuring better representation for women.

The study pointed to the stagnation in the proportion of women elected to the National Assembly from 2003 to 2014, where women made up 25% to 32% of MNAs. The study reiterated that “equality is much more than a law: it is also the way it is applied in day-to-day life that makes it a true value of Québec society.” According to the study, equality in practice requires the elimination of obstacles that hinder or make it difficult for any citizen to become a candidate and have access to an elected position. The 2018 general election reversed this trend, with the percentage of women elected exceeding 40%. This progress, however, is not a given for future elections. We must be constantly vigilant concerning representation by women in politics and also the qualitative aspects of such representation (the work performed by female and male elected representatives and work-family balance, etc.).

Exhibition Aux urnes, citoyennes! Source: National Assembly website, Par ici la démocratie

- ASSEMBLÉE LÉGISLATIVE DU QUÉBEC. Le suffrage féminin : débats sur la Loi accordant aux femmes le droit de vote et d’éligibilité. Législature de Québec, 9-25 avril 1940, Bibliothèque de l’Assemblée nationale, Québec, 1990.

- ASSEMBLÉE NATIONALE DU QUÉBEC. Femmes et vie politique : de la conquête du droit de vote à nos jours, 1940-2010, National Assembly of Québec, Québec City, 2010.

- BRADBURY, Bettina. “Devenir majeure – La lente conquête des droits”, Cap-aux-Diamants, No. 21, Spring 1990, p. 35-38.

- BROWN, Wayne. “Thérèse Casgrain : suffragette, première femme à diriger un parti et sénatrice”, Perspectives électorales, Elections Canada, Vol. 4, No. 1, May 2002, p. 30-34.

- CLEVERDON, Catherine Lyse. Woman Suffrage Movement in Canada, University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 1950.

- COLLECTIF CLIO. L’histoire des femmes du Québec, Quinze, Montréal, 1982.

- DARSIGNY, Maryse. “Les femmes à l’isoloir : la lutte pour le droit de vote”, Cap-aux-Diamants, No. 21, Spring 1990, p. 19-21.

- DIRECTEUR GÉNÉRAL DES ÉLECTIONS DU QUÉBEC. Femmes et politique : facteurs d’influence, mesures incitatives et exposé de la situation québécoise, Québec City, Directeur général des élections du Québec, “Études électorales” series, Québec, 2014.

- LAMOUREUX, Diane. Citoyennes? Femmes, droit de vote et démocratie, Les Éditions du remue-ménage, Montréal, 1989.

- LAPLANTE, Laurent. “Les femmes et le droit de vote – L’épiscopat rend les armes“, Cap-aux-Diamants, No. 21, Spring 1990, p. 23-25.

- LAVERGNE, France. Le suffrage féminin, Directeur général des élections du Québec, Québec, 1990.

- LAVIGNE, Marie. Le 18 avril 1940 – L’adoption du droit de vote des femmes : le résultat d’un long combat, Montréal. Marie Lavigne’s lecture in the auditorium of the Grande Bibliothèque de Montréal on February 21, 2013. Lionel-Groulx Foundation (online). Accessed on April 21, 2015.